Let's talk about another invention that here in the US tries to ignore, put on the back burner, stay away from these types of topics. Even though today the Discovery Channel and History Channel and other scientific discoveries have brought forth this information you just don't see it much today you must go looking for it. And like I said before most people don't go looking for it either because they don't know it exists or people don't use libraries like they used today. This is why we have to have did you call the library and get on the media in which people spend their times to let people know these things do exist. What am I talking about

Sandy Kidd

Above you just watch part 1, part 2 is below.

Ideas for Applying ECE2 to Two Gyroscopes

These are good ideas by Horst, the key new advance in UFT367 to UFT370 is the implementation of code to allow the integration of simultaneous partial differential equations, resulting in a new and detailed knowledge about the motion of a single gyroscope. So the code could be implemented for any configuration of experimental interest. Bold g = – bold Q dot is a very interesting equation. The idea is to get a positive g that would exceed the negative g due to the earth.

Dear Agatha,the Shipov experiment I had in mind is that of Fig. 24 in the overview article I sent over, see attached image. The rotation direction of both gyros seems to be unclear when compared with Sandy Kidd’s construction. We would have to investigate both possibilities which is no problem.Meanwhile I am not sure if the simple construction of Shipov as shown in the figure will work, it may be an oversimplification. The device of Kidd (described in his patent application) is significantly more complicated. It is not clear to me why he changed the angle between the gyro axis by a “cam”. If the angle has to be different from 180 degrees, why did he choose such a small value, and is this value allowed to change during operation?Thank you for hinting to your second device on your web page, two gyros on a scale. This seems indeed to be the most simple experiment. I will propose our group to start with this.Concerning the explanation of the impact of the gyro on gravity: The simplest approach from view of ECE theory would be a comparison with electrodynamics. As you know there is a one-to-one correspondence between the laws of electrodynamics and mechanics. A gyro with rotating masses corresponds to a coil with a circulating current. If the coil is mechanically rotated, the associated vector potential is rotated too. Its field vector A becomes time-dependent, and an electric field E is induced according to the lawbold E = – bold A dot.The same should hold for a gyro under enforced precession. The gravito-magnetic vector potential Q is rotated, leading to an additional accelerationbold g = – bold Q dot.This was my first idea for Shipov-like experiments. It is probably not suited to explain the weight loss of a gyro. I will further think about this. The resonance mechanism described in the latest notes is a candidate but relies on certain resonance conditions. The weight loss of the gyro seems not to require such a condition which indicates another mechanism.Because to my holoday it will take at least two weeks until we can start any experiments here in Munich.Best regards,

HorstAm 04.06.2017 um 03:40 schrieb Dr. Agatha Lorentz-Ferenstein, Ph.D.:Gentlemen,In case you have not noticed by now,the SECOND, simpler, Nobel Prize winning

quantum gravity experiment :is basically a much simpler and technically easierversionof the Sandy Kidd’s device experiment ( see below ).Thank you for your attention, Gentlemen.Dr. Bill Ferrier of Dundee University had this to say

about Sandy Kidd’s device:“ There is no doubt that the device does produce vertical lift.

Several modifications were then made at my suggestions

in order to disprove other possibilities of lift,

particularly aerodynamic effects.”

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Taj4VA1L_vw

- v=MmtOAfrGnw0

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OL_Gasok8xw

- http://www.rexresearch.com/kidd/kidd.htm

- https://beta.groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/caostheory/conversations/messages/14532

I am interested in theoretical opinions of all scientists in our groupin respect to the purported lift effect produced by the Sandy Kidd’s device.In your opinion, is this lift a genuine anomaly?

If so, how exactly your UFT (ECE2) could explain it?And I am NOT asking for any mathematical equations, please!! :))

All I need from you is a short and clear explanation from the standpoint

of general principles of physical phenomena involved :

According to our Quantum Antigravity Hypothesis,

the lift produced by the Sandy Kidd’s device (powered rotors)is a genuine antigravity effect, exactly as understood

and predicted by our Hypothesis.I would even dare to say that it does constitute

an empirical proof of the validity

of our Quantum Antigravity Hypothesis.Looking forward to hear from all of you, Gentlemen.Agatha

If it is so obvious to you, please try to find a precise scientific explanation of how a spinning gyroscope can stay suspended while rotating (precessing) horizontally, or evenbelow horizontal:

“ Scientific discovery consists of seeing what everybody has seen, and thinking what nobody else has thought. Scientific discovery must be, by definition, at variance with existing knowledge. During my lifetime, I made two. Both were rejected offhand by the Popes of that field of science.”

— Albert Szent-Gyorgyi, Nobel Prize Laureate 1937

When the spinning gyroscope is rotating (precessing) horizontally, there is no vertical component of its angular momentum to prevent it from falling under the force of gravity.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j6ExQ4utHEo&t=10m28s

- https://youtu.be/hgjcPnI5qF4?t=3m22s

- https://youtu.be/425fIGX2-68?t=27s

If the spinning gyroscope were to be rotating (precessing) horizontally at a high enough angular velocity, then in this new way it could possibly produce enough of vertical angular momentum to keep it suspended horizontally. However, this is not the case, because as you can see in the video, its angular velocity is too slow.

And the following are two instances of gyro being dropped, and somehow being able to retain its stable operation after being dropped:

So, what keeps the spinning gyroscope from falling under the force of gravity while it is rotating (precessing) horizontally, or even below horizontal?

Clearly, spinning gyroscopes alone, by themselves do not produce any antigravity. So, where this hypothetical antigravity could possibly come from?

For now, let me just say that the above effect is produced by the horizontally spinning gyroscope (angular momentum), which is under the influence of the Abraham-Magnus force.

Mass should be treated on the same footing as energy and angular momentum

An angular momentum synthesis of gravitational and electrostatic forces

Hideo Hayasaka and Sakae Takeuchi of Tokohu University had to counter a series of critical reports by referees before their paper was accepted:

- Anomalous weight reduction on a gyroscope’s right rotations around the vertical axis on the Earth, 1989

- Possibility for the Existence of Anti-Gravity: Evidence from Free-Fall Experiment Using a Spinning Gyro, 1997

Physical Review Letters published their paper 18 months after receiving it, which is an exceptional delay for a journal of scientific letters.” — New Scientist https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg12517042-700-science-does-a-spinning-mass-really-lose-weight/

Mainstream scientists brush-off any gyro “antigravity” effect as nonsense, saying that there is absolutely nothing anomalous there. Everything is fine. That is what plain gyros simply do! If we comb through all the gyro math, we will find no antigravity in them, nor anything else that could come close to “anomalous.” Neither we will find black holes, time travel, or spacetime in Newton’s gravity equation. Fortunately, there is mainstream empirical evidence demonstrating such anomalous effect. Several such experiments have been performed by Prof. Alexander L. Dmitriev, and their anomalous empirical results were described in his research papers:

- https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1101/1101.4678.pdf

- http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1875389212025072

Now, it will be much easier for us to understand what really is going on here:

Dr. Bill Ferrier of Dundee University had this to say about Sandy Kidd’s device:

“ There is no doubt that the machine does produce vertical lift. Several modifications were then made at my suggestions in order to disprove other possibilities of lift, particularly aerodynamic effects.”

- http://www.rexresearch.com/kidd/kidd.htm

- Here's the information in videos again

Research physicist Dr. Bill Ferrier of Dundee Universityexamined the device on campus of the Dundee University. “Its potential is mind-boggling,” Ferrier announced. After Sandy Kidd moved to Australia, a second prototype was tested in Melbourne for three days under the supervision of specialist engineers. Placed in a sealed wooden box, it was suspended from a cord attached to an overhead beam fitted with sensitive measuring instruments. Powered by a model aircraft engine, the entire device due to vertical thrust overcame the force of gravity.

Dr. Bill Ferrier of Dundee University talking about Sandy Kidd’s machine in 1986:

There is no doubt that the machine does produce vertical lift. Several modifications were then made at my suggestions in order to disprove other possibilities of lift, particularly aerodynamic effects.

I am fully satisfied that this device needs further research and development. I have expressed myself willing to help Mr Kidd whose engineering ability is beyond question, and for whom I now have the greatest respect. I am currently trying to interest the university in housing the development and also in finding ‘enterprise’ money to fund the next stage.

I do not as yet understand why this device works. But it does work! The importance of this is probably obvious to the reader but, if it is not, let me just say that the technological possibilities of such a device are enormous. Its commercial exploitation must be worth billions.

In March 1990, Dr. Ronald Evans of BAe Defense Military Aircraft’s Exploratory Studies group, chaired a two-day University-Industry Conference of Gravitational Research, sitting around a table with a gathering of distinguished academics to identify any emerging “quantum leaps” that might impact on BAe’s military aircraft work. Gravity control figured extensively on the agenda.

Imagine it. A technology, popping out of nowhere, that rendered all of BAe’s current multi-billion-dollar work on airliners and jet fighters redundant at a stroke.

The company also undertook some practical laboratory work in a bid to investigate the properties of a so-called “inertial-thrust machine” developed by a Scottish inventor, Sandy Kidd.

In 1984, after three years’ work building his device—essentially, a pair of gyro-rotors at each end of a flexible crossarm—Kidd apparently turned it on and watched, startled, as it proceeded to levitate.

In May 1990, BAe began a series of trials to test whether there was anything in Kidd’s claims, knowing full well that he wasn’t alone in making them.

In the mid-1970s, Eric Laithwaite, Emeritus Professor of Heavy Electrical Engineering at Imperial College London, demonstrated the apparent gyroscopic weight loss.

The accepted laws of physics said that this was not possible, out of the question—heresy, in fact. But Laithwaite’s claims were supported by a top-level study into gyroscopes published by NATO’s Advisory Group for Aerospace Research and Development (AGARD) in March 1990.

The authors of the AGARD report concluded that a “force-generating device, such as Laithwaite’s, if integrated into a vehicle of some kind, could, in theory, counteract gravity. Clearly, if such a counteracting force was of sufficient magnitude it would propel the vehicle continuously in a straight line in opposition to said field of force and would constitute an antigravity device.”

The report went on to say that there was at least one “gyroscopic propulsive device” that was known to work and that the inventor, E.J.C. Rickman, had taken out a British patent on it.

The trouble was, the report concluded, the impulses generated by these machines were so slight they would be useless for all practical applications, except, perhaps, to inch a satellite into a new orbit once it had already been placed in space by a rocket.

It was hardly a quantum technological leap. But that wasn’t the point, Dr. Evans told me. What was being talked about here was an apparent contravention of the laws of physics; the negation, at a stroke, of Newton’s Third Law, of action-reaction. Which was why the BAe sponsored tests on the Kidd machine had a relevance that went way beyond their immediate and apparent value. If there were ways of generating internal, unidirectional, reactionless forces in a spacecraft, and in time they could be refined, honed and developed, the propulsion possibilities would be limitless.

The Incredible Genius Of Eric Laithwaite

By Richard Milton, 2003

Few people visit the Royal Institution, in London’s Albemarle Street, for amusement. There are not many laughs at Britain’s second oldest scientific institution, founded in 1799, where Sir Humphry Davy demonstrated his discovery of the elements sodium and potassium and where Michael Faraday discovered electromagnetic induction. It’s true there have been some lighter moments in the famous circular lecture theatre, especially since Sir William Bragg introduced Christmas Lectures for Children in the 1920s. But, on the whole, this is stuffed shirt territory.

One night in 1973 the stuffed shirts got a shock from which they have still not recovered. It was an experience at which, like Queen Victoria, they were not amused. Indeed it was so unamusing for them that it is the only occasion in the Royal Institution’s two hundred year history that it has failed to publish a proceedings of a major lecture, or ‘evening discourse’. The cause of this unique case of scientific censorship was the maverick professor of electrical engineering of Imperial College, London, Eric Laithwaite.

Laithwaite was no stranger to controversy even before his shadow fell across so distinguished an institutional threshold. In the 1960s, Laithwaite invented the linear electric motor, a device that can power a passenger train. In the 1970s, he and his colleagues combined the linear motor with the latest hovercraft technology to create a British experimental high speed train. This was a highly novel, but perfectly orthodox technology.

The advantages of such a tracked hovercraft are obvious to anyone who sees a hover-rail train running along,suspended in the air above the track — it is quiet, has no moving parts to wear out and is practically maintenance-free. The significance of this last point quickly becomes clear when you learn that more than 80 per cent of the annual running costs of any railway system is spent on maintenance of track and rolling stock because of daily wear. The British government at first invested in the development of his device but later, after a series of budget cuts, pulled out pleading the need for economy. Laithwaite, a blunt-speaking Lancashire man who did not shrink from speaking unpopular truths, told the Government and its scientific bureaucrats the mistake they were making in no uncertain terms, but its decision to cancel was unchanged.

Laithwaite refused to be beaten and took his invention one step further. He designed an even better kind of hover train — one in which his linear motor was levitated by electromagnetism giving a rapid transit system that not only provides quiet, efficient magnetic suspension over a maintenance-free track, but which generates the electricity to power the magnetic lift of the track from the movement of the train.

Speaking in the early 1970s, Laithwaite said of his new ‘Maglev’ system, ‘We’ve designed a motor to propel [the train] that gives you the lift and guidance for nothing — literally for nothing: for no additional equipment and no additional power input. This is beyond my wildest dreams — that I should ever see that sort of thing.’

Laithwaite’s Maglev design was not quite perpetual motion, but certainly sounded enough like something-for-nothing to make the scientific establishment turn its nose up in suspicion. But this project, too, was cancelled by the government and further development was halted. Today, Maglev trains are being built in Germany and Japan but Britain continues to spend 80 per cent of its railway budget on maintenance of conventional transport systems — several hundred millions every year.

With the Maglev project cancelled, the technology Laithwaite had devoted the previous twenty years to developing was put in mothballs. The object of his entire career for decades disappeared overnight. By an extraordinary chance atjust the same time that the Maglev project was cancelled, Laithwaite received an intriguing telephone call out of the blue from an amateur inventor, Alex Jones.

Jones claimed to have a remarkable new invention to demonstrate which he had tried to interest scientists and engineers in, so far without success. Would Laitwaite like to take a look at it? While others had dismissed Jones as a crank, Laithwaite, now with time on his hands, invited him to come to Imperial College.

When Jones arrived in the laboratory he had a strange-looking contraption to show. It was a simple wooden frame on wheels that could be pushed backwards and forwards on the bench top, like a child’s trolley. But suspended from the front of the frame was a heavy metal object that could swing from side to side like a pendulum. The metal object, Jones explained, was a gyroscope.

As Laithwaite looked on in puzzled amazement, Jones started the gyroscope spinning and then allowed it to swing from side to side. The wooden box moved along the bench top on its wheels although there was no drive to the wheels and no external thrust of any kind — something that shouldn’t happen according to the laws of physics.

‘When Alex switched his machine on,’ recalled Laithwaite, ‘it was quite disturbing to one’s upbringing. The gyroscope appeared to be producing a force without a reaction. I thought I’d seen something that was impossible.’

‘Like everyone else I was brought up on Newton’s laws of motion, and the third law says that for every action there’s an equal and opposite reaction, therefore you cannot propel a body outside its own dimensions. This thing apparently did.’

Laithwaite started some gyroscope experiments of his own, making large spinning tops with most of the mass in the rim of the wheel, and he found that, ‘these very definitely did something that seemed impossible.’

It was at this critical point in his career that he was invited by Sir George Porter, president of the august Royal Institution, to deliver a Friday Evening Discourse.

In retrospect it might seem to be rather risky for Sir George to have invited a blunt-speaking and controversial figure to address the Institution. But, until then, Laithwaite’s clashes with the government and scientific bureaucrats over the development of his Maglev train had been a conflict over money and over innovation: not over scientific principles. He had fought the same kind of battle as most senior scientists in Britain for scarce resources. He may have been the sort of outspoken individualist who finds himself in the headlines, but he was still a distinguished professional scientist, still a member of the club.

It was against this background that the Royal Institution invited him to deliver the lecture. But the Friday Evening Discourse is no ordinary lecture. It is a black tie affair, preceded by dinner amidst the polished silver and mahogany of the Institution’s elegant Georgian dining room, under the intimidating gaze of portraits of the giants of science from the eighteenth and nineteenth century, staring down from the panelled walls.

When you are invited to be thus feted by your fellow members of the Royal Institution and to deliver a Discourse from the spot where Faraday and Davy stood, it is usually the prelude to collecting the rewards of a lifetime of distinguished public service: Fellowship of the Royal Society; Gold Medals; perhaps even a Knighthood. In keeping with such a conservative occasion, those invited to speak generally choose some worthy topic on which to discourse — the future of science, perhaps, or the glorious achievements of the past.

But Laithwaite chose not to discourse on some worthy, painless topic but instead to demonstrate to the assembled bigwigs that Newton’s laws of motion — the very cornerstone of physics and the primary article of faith of all the distinguished names gathered in that room — were in doubt.

Standing in the circular well of the Institution’s lecture theatre, Laithwaite showed his audience a large gyroscope he had constructed — an apparatus resembling a motorcycle wheel on the end of a three foot pole (which, is precisely what it was). The wheel could be spun up to high speed on a low-friction bearing driven by a small but powerful electrical motor.

Laithwaite first demonstrated that the apparatus was very heavy — in fact it weighed more than 50 pounds. It took all his strength and both hands to raise the pole with its wheel much above waist level. When he started to rotate the wheel at high speed, however, the apparatus suddenly became so light that he could raise it easily over his head with just one hand and with no obvious sign of effort.

What on earth was going on? Heavy objects cannot suddenly become lighter just because they are rotating, can they? Such a mass can only be propelled aloft if it is subjected to an external force or if it expels mass, in a rocket engine for example. Had Laithwaite taken to conjuring tricks? Were there concealed strings? Confederates in trapdoors?

If Laithwaite expected gasps of admiration or surprise, he was disappointed. The audience was stunned into silence by his demonstration. When he went on to explain that Newton’s laws of motion were apparently being violated by this demonstration, the involuntary hush turned to frosty silence.

‘I was very excited about it,’ he recalled, ‘because I knew I had something to show them that was startling. And I did it rather in the spirit of “come and see what I’ve discovered — come and share this with me.” It was only afterwards that I realised no-one wanted to share it with me. The reaction was “the man’s obviously a lunatic”. “There must be some trick” was what people said.’

‘I was simply trying to tell them, “look, here’s something very unusual that’s worth investigating. I hope I’ve got sufficient reputation in electrical engineering not to be written off as a crank. So when I tell you this, I hope you’ll listen.” But they didn’t want to.’

‘After the Royal Institution lecture all hell broke loose, primarily as a result of an article in the New Scientist, followed up by articles in the daily press with headlines such as “Laithwaite defies Newton”. The press is always excited by the possibility of an antigravity machine, because of spaceships and science fiction, and the minute you say you can make something rise against gravity, then you’ve “made an antigravity machine”. And then the flood gates are unleashed on you especially from the establishment. You’ve brought science into disrepute or you’re apparently trying to because you’ve done something that is against the run of the tide.’

The resounding silence of his audience continued long after that fateful evening. There was to be no Fellowship of the Royal Society, no gold medal, no ‘Arise, Sir Eric’. And, for the first time in two hundred years, there was to be no published ‘proceedings’ recording Laithwaite’s astonishing lecture. In an unprecedented act of academic Stalinism, the Royal Institution simply banished the memory of Professor Laithwaite, his gyroscopes that became lighter, his lecture, even his existence.

Newton’s Laws were restored to their sacrosanct position on the altar of science. Laithwaite was a non-person, and all was right with the world once more.

For the next twenty years, Laithwaite carried on investigating the anomalous behaviour of gyroscopes in the laboratory; at first in Imperial College and later, after his retirement, wherever he could find a sympathetic institution to provide bench space and laboratory apparatus.

By the mid-1980 — what he called ‘the most depressing time’ — Laithwaite had conducted enough empirical research to demonstrate that the skeptics were right when they said that there were no forces to be had from gyroscopes. ‘The mathematics said there were no forces and that was correct’, Laithwaite recalled. The thing that wouldn’t go away was:

can I easily lift a 50 pound weight on a long shaft over my head with one hand, and with no obvious sign of effort, or can’t I? Of all the critics that I showed lifting the big wheel, none of them ever tried to explain it to me. So I decided I had to follow Faraday’s example and do the experiments.

After retiring from Imperial College, Laithwaite began a long series of detailed experiments. Sussex University offered him a laboratory and he formed a partnership with fellow engineer and inventor, Bill Dawson, who also funded the research. Laithwaite and Dawson spent three years from 1991 to 1994, investigating in detail the strange phenomena that had unnerved the Royal Institution.

‘The first thing I wanted to find out was how I could lift a 50 pound wheel in one hand. So we set out to try to reproduce this as a hands-off experiment. Then we tackled the problem of lack of centrifugal force and the experiments were telling us that there was less centrifugal force than there should be. Meanwhile I started to do the theory. We devised more and more sophisticated experiments until, not long ago, we cracked it.’

The real breakthrough came, said Laithwaite, when they realized that a precessing gyroscope could move mass through space. ‘The spinning top showed us that all the time, but we couldn’t see it. If the gyroscope does not produce the full amount of centrifugal force on its pivotin the centre then indeed you have produced mass transfer.’

‘It became more exciting than ever now because I could explain the unexplainable. Gyroscopes behaved absolutely in accordance with Newton’s laws. We were not challenging any sacred laws at all. We were sticking strictly to the rules that everyone would approve of, but getting the same result — a force through space without a rocket.’

The research of Laithwaite and Dawson has now borne practical fruit. Their commercial company, Gyron, filed a world patent for a reactionless drive — a device that most orthodox scientists say is impossible.

Sadly Eric Laithwaite died in 1997. His device remains in prototype form, comparable perhaps to the Wright Brother’s first aircraft or Gottlieb Daimler’s first automobile.

Shortly before his death, Laithwaite spoke philosophically about the long experimental road he had trudged virtually alone.

Why should people reject the idea of something new?’ he asked. ‘Well, of course, they always have. If you go back to Galileo, they were going to put him to death for not saying the earth was the centre of the universe. I’m reminded of something that Mark Twain once said; ‘a crank is a crank only until he’s been proved correct.’

‘So now I myself have demonstrated that I’ve been correct all along. Anyone seeing the experiments would know at once, if they knew their physics, that I’ve done what I said I could do, and that I’m no longer a heretic.’

Laithwaite’s reactionless drive is an extraordinary machine; a machine that orthodox science said could never be built and would never work. But though it may well eventually prove of great value — perhaps even providing an anti-gravity lifting device — it is a net consumer of energy, just like Griggs’s hydrosonic pump. There is no evidence at present that it is an over-unity device — merely a novel means of propulsion that proves there are more things in heaven and earth than are currently dreamed of by scientific rationalism.

The U.S. government has long sought to control the release of new technologies that might threaten the national defense and economic stability of the country. During World War I, Congress authorized the United States Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) to classify certain defense-related patents. This initial effort lasted only for the duration of that war but was reimposed in October 1941 in anticipation of the U.S. entry into World War II. Patent secrecy orders were initially intended to remain effective for two years, beginning on July 1, 1940, but were later extended for the duration of the war.

The Invention Secrecy Act of 1951 made such patent secrecy permanent, though the order to suppress any invention must be renewed each year (except during periods of declared war or national emergency). Under this Act, defense agencies provide the PTO with a classified list of sensitive technologies in the form of the "Patent Security Category Review List" (PSCRL). The decision to classify new inventions under this act is made by "defense agencies" as defined by the President. Generally, these agencies include the Army, Navy, Air Force, National Security Agency (NSA), Department of Energy, and NASA, but even the Justice Department has played this role.)

to hold any More Public experiments top secret to produce what is shown in the video below.keep in mind this is just a representative on what could be possible given all that we know or has been given to know.

there are works different but on the same level as the experiments that we are researching

it is why we are performing as many experiments as we possibly can hear at Media Library

Keep your imagination as fluid as you can and do the experiments to the best of your abilities, then go just beyond to create something new

Gyroscopic Propulsion rebuttal or!

| Warning - Gyroscope propulsion is currently just speculative research and is not accepted by the scientfic community. These propulsion pages should be regarded separate from the rest of the site. |

What do these "Propulsion devices" do?

The concept is to produce a gyroscope based device that can produce sufficient amounts of lift/force to be detectable and useful. In an extreme case this may mean that the machine could lift its own weight and hence is able to fly or just to push something along. However research is still in its early stages and I've yet to see one that can create any force under proper test conditions.

The use of the term "Anti-Gravity Device"

The use of the term "Anti-Gravity Device" is sometimes associated with this type of device. This is misleading and confusing in many ways and I don't believe the term should be used. It is highly unlikely that these type of devices effect gravity in any way. I believe the forces are independent of gravity and more related to the gyroscopic forces. From the evidence I’ve seen, if these devices really do produce force I believe energy is some how converting from rotational energy to a linear thrust.

Then these 'machines' can be put to better use in space with a zero or micro gravity environment.

Are these devices related to zero point energy?

As far as I'm aware none. In fact great amounts of energy has to be put in to get any linear force out (if any).

Uses for gyroscopic propulsion devices

Gyroscopic propulsion would have a number of uses on land, sea, air and space. What uses the device can do depends on the amount of force produced and its efficiency to produce that force. It may turn out that they can only ever produce a force a fractional of the weight of the device e.g. a 10Kg device give 1% thurst = 100g thurst. The weight to thrust ratio will define whether the technology can be used on land, sea and in the air.

However in space the devices come into there own and they would be useful even if they could only produce a small thurst compared to theier mass. Rockets are used almost exclusively as a means of propelling something in space and although inefficient, it is the best we have at present. Assuming gyroscopic propulsion does work it provides a means of getting from A to B in space without taking your fuel up too. The devices could simply be solar powered so the fuel won't run out. Of course the device still needs a way to get it into space in the first place.

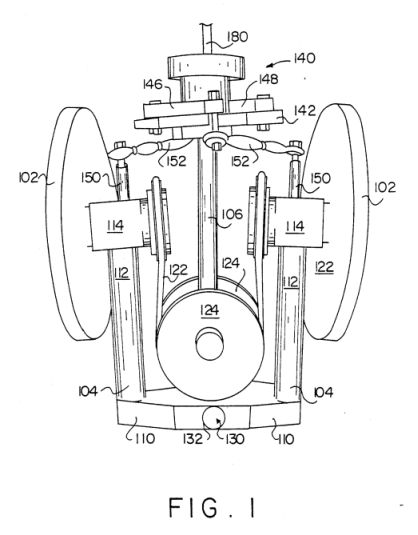

Sandy Kidd and Force Precessed Gyroscopes

A simplified description of force precessed gyroscopes

In the following set of diagrams red arrows are used to show the force applied to the structure. Provided the gyroscopes themselves are rotating in the correct direction (not shown on diagram) the gyroscopes will produce a counter-acting force known as precession, as shown in the diagram as two blue arrows.

Normally this would produce a continuous torque as the whole device is revolving which would cancel it self out in the form of stress in the structure of the machine. However in Sandy's patent the gyroscopes are pushed in/out using cams resulting in the following motion (represented by the eight diagrams). As far as I can understand a number of up-ward pulses are produced due to the two gyroscopes (in this particular case, more can be used) exerting a force towards the centre of the structure (axle). This in effect is a vastly simplified version of what is going on. A number of independent tests have shown results for and against the machine.

SIDE VIEW

TOP VIEW

Jacket photographs: front; Topham Picture Source/Carolyn Jones: back; Fotopress, Dundee

Image: Copyright Grampian Television PLC

While working in the Air Force, Dundee based engineer Sandy Kidd was one day taking a gyroscope out of an aircraft. Not realising that the gyroscope was still running, he came down the steps of the aircraft and turned at the base of the steps. At this point the gyroscope almost threw him across the floor. This stirred his interest in gyroscopes, Sandy spent many years and tens of thousands of pounds in his garden-shed/garage developing and working on gyroscopic devices. Trying to get a number of gyroscopes to react against one another to produce lift. In time he developed a device that he claimed could achieve this. Building other models using that principle and discussing his ideas with others, he came to conclusions of how it worked. Dundee University was interested in the invention and for a time worked with him, but long term could not supply the funds or enthusiasm that was needed. He tried obtaining funds to develop his invention in Scotland, but had to resort to looking for funds elsewhere. An Australia corporation BWM took the task on to develop a gyroscopic propulsion system but unfortunately the company went bust. British Aerospace has also been involved in the research with him but dropped the funding.

A UK/European patent for his invention was applied for (I have a copy of the application). I did try to find a granted patent for Europe but without success. I ended up phoning the European patent office to find out if one was granted. I was told that it would have been, but it was withdrawn at the last moment (funding dropped). I did however find a granted US patent (5024112). The fees for the patent have stopped being paid for some years ago. Which means anyone is free to copy, sell etc his invention (At least in the US/Europe).

Sandy is still working on various devices based around gyroscopes and hopefully we will be seeing more inventive designs from him in the near future.

Image: Copyright Grampian Television PLC

Dr Bill Ferrier of Dundee University talking about Sandy Kidd's machine in 1986:

"..............There is no doubt that the machine does produce vertical lift. Several modifications were then made at my suggestions in order to disprove other possibilities of lift, particularly aerodynamic effects.

I am fully satisfied that this device needs further research and development. I have expressed myself willing to help Mr Kidd whose engineering ability is beyond question, and for whom I now have the greatest respect. I am currently trying to interest the university in housing the development and also in finding 'enterprise' money to fund the next stage.

I do not as yet understand why this device works. But it does work! The importance of this is probably obvious to the reader but, if it is not, let me just say that the technological possibilities of such a device are enormous. Its commercial exploitation must be worth millions."

Professor Eric Laithwaite

(14th June 1921 - 27th November 1997)

Image: Copyright Grampian Television PLC

Geoff Russell (Geoffrey C Russell)

July 1999 I got in contact with Geoff Russell (Patent No.2,090,404). He tells me that the machine based upon his patent has changed quite a lot. Vast improvements have been made over the years and he now has a device that he says "weighing 22lb, which was able to consistently register weight loss or vertical lift pulses of 20lb, give or take the odd oz".

He has very kindly given me diagrams and notes on one of the ways that he tests his devices

"Notes on Fig 1 Vertical Lift Weighing Board

Fig 1 is designed to detect and measure any vertical lift being generated by your machine. This is achieved essentially by providing a stable base on which to test your apparatus. While leaving the base and apps free to tilt vertically upward, in response to any vertical lift being generated.

Fig 1 consists of a flat rigid wooden board approx. 1" Thick, the overall size of which should be determined by the size and weight of your own apparatus. The board has two L shape aluminium sections attached to its underside. With the first positioned at the central pivotal axis and the second positioned at one end of the board. A contact switch is attached to this aluminium section so that it operates, lighting an indicator lamp each time the board tilts upward loosing contact with the ground.

A counter weight approx. the same weight as your apparatus is also required to vary the balance of the board. By varying the position of the board movement of the counter weight towards the central pivotal axis of the board, would mean that your apparatus would have to generate greater vertical lift to light the indicator lamp. Moving it away from the control axis has the reserve effect.

To determine how much vertical lift your apparatus is generating, you must use a spring balance to measure how much upward force is required to raise your apparatus sufficiently to tilt the board upward, lighting the indicator lamp. The reading you get is the amount of vertical lift your apparatus is generating. You should make a position on the board at which your apparatus is placed for all tests, including the measurements you take before each test to determine how much weightless or vertical lift is required to light the indicator lamp...

...Geoff Russell July 1999"

Geoff Wilson and the Wilson-Fourier Impulse Engine

Website: http://www.sbbg.demon.co.uk/

Geoff Wilson is part of team working which have been experimenting with gyroscopic engines for some 20 years. They now beleave they finally have both the mathematics (copyrighted 1999) and the principals fully understood. They hope to exploit this new engine commencing Y2k. Hopefully more details will be released soon.

No comments:

Post a Comment